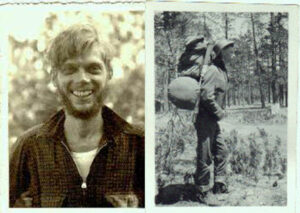

Written by Travis Knight

Waking up was not nearly as difficult as I had expected, considering that I only slept for 3 hours the previous night. Nevertheless, pulling my eyelids upward was the easy part. Getting my body to follow was an entirely different ball game. The smell of coffee conjured my muscles to twitch, and then finally activate. I followed the sweet aroma into the kitchen where I found Jeesh and Sop excitingly talking about the adventure that we were about to embark on. They both had mugs with steaming tops and before I said a word, I found the coffee machine and poured myself a cup. Then I hugged Jeesh, as I had not seen my old friend in years. One sip of hot brew dusted the sleep off of my mind, and once the barrier was broken, the adrenaline hiding beneath sprang to life. Excitement shook my bones, for I knew that it would only be mere hours before I would be in the backcountry with my brothers, with only a pack on my back, and the noise of civilization behind me.

“I chuckled to myself at the irony of it all.”

We quickly did an inventory of our gear and then we were off. It was 5:15 a.m. when we left Sop’s house. Sop’s little single cab truck was full of good spirits, with conversations of catching up, too many cigarettes, and the exhilaration that long beat out our sleep deprivation. Before I knew it, we were getting off of I-80 westbound at the exit titled “Castle Peak.” When I actually noticed where we were, I couldn’t believe it. Across the road, on the I-80’s eastbound side, was Donner Summit—the exact parking lot where I had truck trouble the night before. It turns out, I would have probably gotten a lot more sleep had I just car-camped it. Sop had actually suggested that I just stay put, but I had scoffed at the idea because I thought I would get a better night’s sleep had I just driven to Sop’s house 45 minutes east. I chuckled to myself at the irony of it all.

Not far from the exit, we were already bumpily making our way up a dirt road. Aside from it being 6:00 a.m., we were making even better time thanks to Sop and his truck’s 4 x 4 capability. On AllTrails, the 7.55 hike to the lake starts just a stone’s throw away from the freeway exit. However, with Sop’s little GMC, we were able to shave about 2 miles of that off—saving time and energy. Once parked in that little turnout, we only had 5 miles or so of hiking until we would reach camp. Sop’s truck saved the day.

The dirt road we were on, known as the Castle Valley Trail, weaved uphill through dense foliage and then would open up where we could see the long roaming landscape ahead. After about a mile, Castle Valley Trail ended, and off to the left, a smaller trail snaked its way further into the mountains. This was the trail that would take us to our destination, the famed Pacific Crest Trail that crawls from Mexico all the way up the west coast and into Canada. Commonly referred to as the PCT, the establishment of this interstate trail has a history longer than the trail itself.

Known as the “father of the PCT,” Clinton C. Clark had a vision of one trail that could connect them all. He did this by creating the Pacific Crest Trail Conference, originally established in 1932. For 25 years, Clark led the PCT Conference, bringing together avid hikers, nature enthusiasts, famous photographers, and outdoors-loving organizations—many of which still exist today, such as the YMCA and the Sierra Club. During his 25 years as president of the PCT Conference, Clark and his colleagues successfully connected six existing trails:

- Washington State’s Cascade Trail

- Oregon’s Skyline Trail

- Nor Cal’s Lava Crest Trail

- California’s Tahoe-Yosemite Trail and the famed John Muir Trail

- So Cal’s Desert Crest Trail

He did this with the help of Warren Rogers, a dedicated outdoorsman of the YMCA, who would lead a band of hikers from Pasadena all the way up to Canada… well, eventually. They would do sections every summer. Trekking for days through off-trail breaks between the existing trails, it took 4 summers of arduous hiking and meticulous documentation to accomplish such a feat. This legendary journey is remembered by history as the YMCA PCT Relays of 1935-1938, a huge expedition led by Rogers and a cast of all kinds of other remarkable characters. These back-country pioneers proved that by connecting various west coast trails, dedicated hikers could successfully make the trek from Mexico to Canada (a tradition still practiced today). However, it would take nearly three decades before their efforts would officially pay off.

In February of 1965, just months after he proposed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, a disaster that escalated American involvement in the Vietnam War, President Lyndon B. Johnson proposed an act that actually benefitted Americans. The President called for efforts to strengthen recreational activities, which would be written into law 3 years later as the National Trails System Act. This law would establish America’s National Trails System, which today is “more than 88,600 miles long and consists of 11 National Scenic Trails, 19 National Historic Trails, 1,300 National Recreation Trails, and seven side and connecting trails.” Among the first-ever scenic trails was the Pacific Crest Trail, its only partner at that time being the Appalachian Trail. Today, the National Trails System Act is still the blueprint for trail maintenance by the USDA. However, the act likely would have faded away if not for the efforts of the Forest Service, Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, and the Pacific Crest Trail Association established in 1992.

As our steps pattered along the historical PCT trail, our heavy panting grew with each passing minute. The air was cool and came in pleasant intervals of gentle breezes. For the first part of the trail, though, there was no tree cover. So, although the morning air was blowing through our strained smiles of gritted teeth, our eyes were squinted from the blaring sun above. Every uphill stretch was excruciating, but from the laughter that slipped out between intervals of our heavy breathing, one could gather that we were enjoying the pain. We were feeling the altitude, the climb, and the cigarettes we all had been smoking for most of our lives, and it was painful, but the pain felt damn good.

After 20 minutes or so, Jeesh and Sop spotted a lookout off to the left and quickly shot off the trail to investigate. The lookout was breathtaking, figuratively in the eyes and literally in the lungs. We pulled out tumblers full of ice-cold water and each took a long pull. Water never tasted so great. The bold and brisk liquid quenched our parched gullets. Already, we had seen several streams, shimmering gold between the blue ripples of moving water. Knowing that there was plenty of water, we took healthy swigs from our jugs and headed back to the trail.

“The last thing we wanted to do was trample a little Yellow-Legged Frog, the poor little bastards.”

For most of the next hour of hiking, we traversed a ridge, just under 8,000 feet, with a view one can find within the front and back covers of National Geographic. Then suddenly, we stood over a large valley, down below, bustling with bright blue streams that veined through the lush green landscape, with yellow and purple patches of wildflowers speckled across the high meadow. It didn’t take long to make it down the switchbacks leading into this fairytale setting.

Once we entered the large meadow named Round Valley, we were met with signs warning us to stay on the trail. It turns out that Round Valley is home to one of the Sierras’ endangered species, the high-elevation Yellow-Legged Frog. This rare creature once roamed in vast numbers in many different regions of the Sierras, making homes out of high-elevation bodies of water. However, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife explains that this small frog was nearly wiped out due to the “introduction of non-native fishes, pesticides, ultraviolet radiation, pathogens, acidification from atmospheric deposition, nitrate deposition, livestock grazing, recreational activities, and drought.” Today, with the efforts of CA Fish and Wildlife to create “fish-less habitats,” the frogs have steadily started to make a come-back, according to a conversation that the Tahoe Daily Tribune had with Dr. Roland Knapp. Even though it was enticing to charge into the sheer beauty of Round Valley, we heeded the signs and stayed on the trail. The last thing we wanted to do was trample a little Yellow-Legged Frog, the poor little bastards.

Not far down the trail through Round Valley, to our left was something large hiding behind the trees. We stopped, took a short water break, and headed off to see what this mystery structure was. What we walked up on was the Peter Grubb Hut, a lodge-looking structure wrapped in pine and rock, with a wooden ladder leading to a small second-floor door, and a single solar panel hanging from its brown corrugated roof. We figured it was some kind of historical building that is not meant for public use. However, we were wrong.

The Peter Grubb Hut was named after the avid mountaineer, Peter Grubb, a man who lived a very short life, dying from unknown causes in Europe in 1937. Although he died young, Grubb had countless mountain adventures, and “seemed to pack a long lifetime of living in those 18 years” he had, as remembered by his sister, Elizabeth Grubb Lampen in 2004. The hut—back then known as the Clair Tappan Lodge—was frequented by Peter Grubb, as he and his friends would stay there while skiing in the wintertime. In tribute to his many adventures, the Sierra Club renamed the Norden ski lodge after Peter Grubb.

Today, the Peter Grubb Hut can be rented by as many as 20 people via reservations as a winter lodge destination. It is also a beacon of shelter for hikers who may get caught in a snowstorm. In the summertime, one may find trail mixes and granola bars for hungry hikers. By now, our packs were off, and we were climbing the wood ladder to see what was inside. We saw some snacks inside, but figured we would leave them for someone who may need them more than us. We strapped our packs back on and continued down the trail toward Paradise Lake. The site of the snacks, though, seemed to activate our hunger because not even 15 minutes later, we were all hungry. It was time for lunch.

Not much further down the trail, after leaving the mystic Round Valley and heading into thickly forested trails, we found a perfect spot for lunch. A small wooden sign declared that we had made it to “Unconformity Spring.” The spot was heavily shaded and had a rushing stream just feet from the trail. We let our packs down and each grabbed one of our freeze-dried meals. A good lunch was indefinitely called for.

First, we gathered water from the ice-cold stream with my water filter bag. Getting the water from inside the bag and into your cup is not a quick process, so we used the remaining of our water in our tumblers to cook our lunches. Then we refilled our tumblers while we ate. As the hot food warmed up our stomachs, the only sound surrounding us was the rushing stream, the dripping of water into the metal tumbler, and the trees being gently pushed by the breeze overhead. Once our tumblers were full of water, and our stomachs full of food, we quickly cleaned up, packed our backcountry cutlery back into their homes, and got back on the trail; now hydrated and rejuvenated.

By now, Jeesh and Sop had to have been so annoyed with me. When I’m excited and amped up, I don’t shut the fuck up. I talk and talk and talk. Hell, I talk a lot when I am not hyped up. By now, my two hiker-buddies were mostly quiet. So, I talked enough for all three of us. And not actually saying anything either… just talking to hear words come out of my mouth. I probably said “TRY IT AWT” over a hundred times. However, if Jeesh and Sop were annoyed, they didn’t show it.

After leaving Round Valley, the hiking was stepped up a notch. The vibrant green meadow, with its blue sparkling streams and wildflowers of purples, yellows, and reds, was quickly behind us. In front of us were uphill, dusty trails heading into switchback terrain. Round Valley is somewhere around 7,800 feet. We were now climbing into higher elevations in shorter spurts. I put my head down and watched my feet as each shoe heavily stomped the trail. The sweat on my nose and forehead was gaining speed in its falling, the drips and drops raining down on the dusty trail below. To ignore the growing pain in both of my legs, shoulders, lower back, and now throbbing feet, I concentrated solely on my breathing. Although the breeze was pleasant and sweet to the skin, I only could hear my breathing. I peered up and saw Jeesh and Sop really pushing for it, heads down, breathing heavily.

In the high country, it’s not just the uphill part that gets you. The oxygen levels are already low, and as you climb up at a fast rate, it gets harder and harder to breathe. The process is a bit painful, especially for three dudes who are doing this kind of thing for the first time and aren’t in the best shape of their lives. However, behind the gasping breaths and the build-up of weakness, growing and growing in the calves, each one of us wore a smile. Endorphins were raging through our brains like snow melt rushing downhill in the summer heat, and the visuals we would catch of the vast valley beyond, polka-dotted with crimson-blue lakes, was enough to bring tears of joy. At some point, the uphill battle simmered down into a more forgiving trail, cruising along a ridge line, and offering an eagle’s view of the land. We came to a point where it looked like we were about to start heading down, into another valley below. We thought this would be a good place to take a water break.

As we stood catching our breaths and taking conservative sips of water—there were no streams up here—we looked out over the mountains, with valleys crawling around them and little lakes scattered across the landscape. One lake, however, was huge. Although it was the farthest lake from us, it was the largest.

“That’s Fordyce, I think,” Sop said.

“You think?” Jeesh was now analyzing the faraway body of water. He looked around and seemed to understand where he was standing. “Dude, I think you’re right.”

“Yeah,” Sop said excitedly, “That’s definitely fuckin’ Fordyce. It has to be!”

“I agree,” Jeesh said. “It makes sense.” I had no clue what they were talking about. They explained that Fordyce is a big lake where droves of people camp during the summer. They had both been there but weren’t too exuberant when talking about it. Either way, I was blown away. I thought it was so cool that they understood where they were, especially out there, where the miles and miles of mountains can start to get dizzying, like being on the ocean with no land in sight. Mentally, I was definitely taking notes. It was as if these dudes had a built-in GPS in their heads. I kept my admiration to myself, took one more sip of my water, and we were off. Once in the research process of writing this very story, I found out that Jeesh and Sop were right. It was Fordyce Lake.

“But make sure you find that sign. Otherwise, you might be in trouble.”

Now the hiking was easier on the calves but harder on the toes. We were heading downhill at a pretty rapid rate. The dusty trail of the bare granite ridges we had been traversing had now turned into soft brown soil, and we were surrounded by huge pines and baby Sequoias. Before, we could almost see miles ahead of us. Now, we could barely see 50 feet before the winding trail would hook left or bolt right, deeper into the forest. An older couple passed us, and I asked:

“Are we getting closer to Paradise Lake?”

The husband replied, “Oh yeah, you’re not far now.”

“Oh. Awesome. Thanks!” We had almost walked completely away from them, turning the next bend, when the wife shouted: “Hey, make sure you find the sign!” Simultaneously, the three of us stopped.

“What sign?!” Jeesh shouted back. The couple had stopped, and we were slowly making our way back to them.

“About a mile up there, the trail splits into three directions. There is a sign nailed to a tree; pretty hard to see. Once you get there, you’re really close to the lake. But make sure you find that sign. Otherwise, you might be in trouble.” She laughed and her husband did too.

“Yeah, if you miss the sign,” he said with a chuckle, “you guys won’t be making it to Paradise today. That’s for sure.” We all laughed, thanked them, and continued on our way.

“I noticed another trail jetting off to the left. Jeesh and Sop had already passed it.”

Not long after we met the kind older couple, we found ourselves in another awe-inspiring meadow. Streams were everywhere, tall green grasses loomed around us, butterflies danced their fluttering waltz, and the only sound that would interrupt the clear blue rushing water was the snapping of the crackling forest grasshoppers that hopped in dodge from our moving feet. We crossed a wooden bridge and then headed into another heavily forested area. It was a densely wooded area, and at one point—me walking in the back of our convoy—I noticed another trail jetting off to the left. Jeesh and Sop had already passed it.

“Yo, guys. Hold on.” I stopped, and both Jeesh and Sop stopped and turned to look back at me. “There’s a trail right here. I think this is the place where those people told us to look for that sign.” Having seen the other trail, veering off to the left, Jeesh and Sop agreed.

“I don’t see it. You think this is the spot?” Jeesh questioned.

“Yeah,” Sop agreed, “I don’t see no fucking sign.”

“It has to be the spot,” I said. “I mean, look. There are two trails.” Jeesh and Sop agreed with me but remained skeptical. If I was wrong, then I was slowing us down. And if we wanted time to hike Paradise Valley, we would need to get to camp earlier than later. Every minute counted. Then I saw it: a small sign, the same color as the bark of the great pine it sat nailed to, almost magically and suddenly, became visible. It said “Paradise Lake –>” and all of a sudden, the trail became apparent—although it had been there the entire time, staring us in the face, hidden in plain sight. I felt good. Up until then, I hadn’t really contributed too much, except for the meaningless babbling and stupid jokes that would catch a laugh here and there. But now, I felt like I had contributed to the pack.

“Fuck yeah!” Jeesh exclaimed.

“For real,” Sop added. “Good job Trav. We would’ve been fucked.” We all laughed and trekked forward. We were getting close, and we could feel it.

“What was once a blatant trail, either carved into a ridge or surrounded by tall grass, was now submerged in complete chaos.”

Soon after the three-way fork and the camouflaged sign, the trail completely disappeared. What was once a blatant trail, either carved into a ridge or surrounded by tall grass, was now submerged in complete chaos. All we could see were large mounding boulders of granite. We stopped.

“Wait,” warned Jeesh, “This dude I work with told me about this part. He said to be careful right before you get to the lake, that there is a wash.” A wash is when the trail seems to “wash” away in multiple different directions. When caught in a wash, everything looks like a trail. This was my first time dealing with such an obstacle, and the experience was dizzying, disorienting, and a bit scary. Jeesh continued. “Yeah, this is definitely it. Seppi!” Sop had not heard Jeesh and had swiftly scurried to higher ground. “Yo, Sep! I think we fucked up, man. I think we’re off the trail.” I felt completely out of my element.

“Well,” Sop was now standing on a large granite stone, pointing out in front of him, “I think I see the lake Jeesh. I’m pretty damn sure it’s right over there!”

“Dude! Sep, just come down! Let’s just find the trail man!”

“Jeeesh! The fuckin’ lake is RIGHT THERE!” Jeesh and I looked at each other, shrugged, and climbed up to Sop’s vantage point. He was right. The lake was “fuckin’ right there!”

With Paradise Lake now in view, we no longer cared about the trail. We simply climbed rocks to move forward, keeping the brilliant blue surface of Paradise Lake always in our view. It probably took 15 minutes, and we were standing on the granite shore of Paradise Lake, the small Paradise Lake Island was within swimming distance. We had made it, but we weren’t done yet.

There were already some campers, and we could see their tents scattered, bold and green and brown, protruding in the milky white of the granite. We thought it wise to check out the other side of the lake—the southeast point. We figured it was more difficult to get there, so we hoped that there wouldn’t be many campers on that side—not that there were a ton of campers on this side. But out there, people keep their distance. That’s just backcountry etiquette.

I had never seen a lake like this. I mean, the water reminded me of Lake Tahoe—which was actually not far from where we were now standing—but the white granite, the twisted pines, and the randomness of this lake were just spectacular. All day, we had seen lakes way off in the distance, and most of the scenery was trees and valleys and meadows, so for this immaculate thing of beauty to just seemingly appear was truly awestriking.

Getting to the southeast part of the lake was not easy. We had to actually scale and climb large slabs of granite to get there. Climbing is fun, don’t get me wrong, but it can get a little sketchy with 30 lbs. on your back. During our last stretch, we found a cool-looking rock jump, and across the water, swimmable and on the southeast shore of the lake, we saw a promising campsite. Just 10 or 15 minutes later, we were on the other side of the lake. Finally, after a long journey that started at 5:00 am at Sop’s house that morning, we made it to Paradise Lake. Full of relief and reward, we dropped our packs and set up camp. We were home free.