Written by Travis Knight // Photography by Camila Pereira

Milla and I didn’t wake up until noon, with severe hangovers bludgeoning our brains. By the time we actually got our asses moving, it was ten past one. By the time we actually got to the trailhead, it was well past two. We had definitely blown it on time. To successfully complete the trail in two days, we needed to camp in Big Basin that night. We had easily done 10-mile day hikes in the past, so if we pushed ourselves, there was a chance of making it. In the case of us not making it, we would just have to wake up super early the next day and make up for the lost time. No problem.

Immediately, we were faced with our first unseen variable. It turned out that we were far from the only people who had thought a nice day in the hills with fresh air would be a good getaway from the contaminated valley below. Droves of masked faces littered Castle Rock state park that hot Saturday afternoon. To make matters worst, the new way of life that COVID had bestowed upon humanity seemed to also make its way into the hills. There were signs everywhere saying to stay six feet apart. This would have been no challenge if the park had not carved out designated, one-way trails to direct throngs of day hikers and climbers. It was apparent that the “new normal” had found its way into nature. Within fifteen minutes of feeling like I was walking through a city, not the wilderness, I became restless and dared to take a shortcut. Instead, of cutting distance, though, I added it on.

After I took the “shortcut,” a scowling couple approached us from up ahead. Then a sign scolding us for going the wrong way appeared through the circumjacent bushes. Milla was frustrated with my manic decision to cut corners, and I was frustrated because it had already been an hour and we had not even made it out of Castle Rock.

Thus far, this was not a peaceful or relaxing experience like we had imagined. We were bickering, and every several passing moments, a couple or group of people would be coming towards us from around the next bend. Their masked faces hid their frowns, but their livid eyes gave away their true feelings. Sometimes people would appear so suddenly that Milla and I would not have time to put on our masks. I was just waiting for someone to fustigate us at any moment, for either going the wrong way, not wearing a mask in the forest, or both. Fortunately for us, like the germs ravaging the way of life, the rage never broke through the puny face cloths.

“My stress was now turned on high; we had only covered three miles in two hours.”

Soon after we passed the notorious “Goat Rock,” the crowds of people dissipated until we saw no other fellow hikers. We had left the Ridge Trail long behind us, and now had reunited with the Saratoga Gap Trail, the long trail that would ultimately spit us out onto the “Skyline to the Sea Trail.” We were doing terribly on timing. It was now 4 p.m. and the sun was high in the sky, unforgiving and basking us with a heckling heat. The view was beautiful as we looked out over the broad Santa Cruz Mountains. Milla was taking her time, stopping for breathtaking scenery, snapping pictures, and just taking it all in. Of course, in my dickhead-mind, this was her dragging feet. My stress was now turned on high; we had only covered three miles in two hours.

Bend after bend rolled onto us from the never-ending ridge line. We were heading northwest for what felt like hours. I was feeling the strain in my upper back and now realized that I was carrying way too much weight. I had brought a lot of unnecessary things, a heavy hatchet being one of those items. Behind me, I could hear Milla grumbling about the heat and her heavy pack. Finally, the ridge line ceased and hooked northeast into the thick forest. We made it to Main Camp by 5 p.m.—our planned timeline had now completely vanished. Originally, we planned on setting up camp—in Big Basin, mind you—at this time. And here we were not even a quarter of the way. I was flustered, to say the least, but I kept my complaints to myself and pushed forward.

Aside from the occasional complaint about her backpack, Milla seemed content. Oblivious to the time whirling by us—at least that’s what I thought—Milla kept her spirits high by shooting photos, giggling from whatever she would mumble to herself, and forcing a smile on her wearied face. Her cuteness was alleviating my own snapping patience. At one point I just accepted that we would likely be walking in the dark. Fuck it, I thought. At least we’re out here. Just enjoy it. But no matter how hard I tried, inside, I was freaking out.

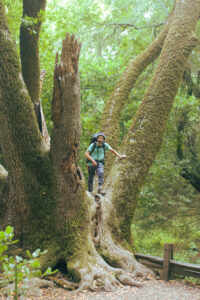

The next 3.5 miles were smooth. A thick forest of eerie coast live oaks, twisting manzanitas, dense arroyo willows, and towering knob cone pines—to name just a few—surrounded us. Paired with the now fading sunlight, we were immersed in a now cool and pleasant hiking experience. Also working to our advantage was the easy walking of the trail. The never-ending ridgeline was lumpy, presenting us with a lot of up-and-down hiking—the former hard on the legs while the latter is tough on the toes. This part of the trail was smooth, mostly flat with dense foliage for protection. The air was cooling with a change of smell in the forest. To my right, I heard a car zoom past on the nearby Highway 9. And then like a spontaneous treat, a small grove of redwoods popped into view. Were we getting close to Big Basin? No way, I thought.

The redwoods were so closely grown together that they looked like a family, with larger parent trees looming over their offspring. Although the image of a family in my mind was solely based on my subjective imagination, the word family was not unlike what we were actually peering up at.

This grouping is caused by the coastal redwood’s to reproduce “by means of seeds and stump sprouts.” A mature tree will drop small cones—much smaller than their Sierra cousins—equipped with tiny seeds numbering around 60 or so. Since the Santa Cruz forest runs rampant with other tree species, the forest floor is covered with green waste—leaves, twigs, branches, etc. Because this is an unlikely environment for speedy germination, the coastal redwood came up with a trick: stump sprouts. This is when the seeds are nurtured by older nearby stumps or living roots. Many other trees do this, but none more blatant than a bundle of gargantuan redwoods. This stump sprouting is why the coastal redwood will grow in a close group like the one Milla and I had stumbled across. So, they weren’t like a family, they actually were a family.

After Milla snapped a few shots, the moment of awe-inspiring bliss was quickly replaced with panic. It was nearly 7 p.m. and even if we had made it to Big Basin—which was now impossible—we did not know how far the nearest camp was. Both Milla and I were slowing down. Our legs were screaming at us to stop and sit down while our backs creaked, and our feet swelled. We had come prepared as far as supplies went. In fact, we likely went over-prepared. Physically, though, we were nowhere near prepared.

Distant sounds of cars continued to whoosh by somewhere above that was unseeable to us below. A mangled SUV likely fled by a drunk driver sat lonely and abandoned, nose crushed into a tree, like a fallen soldier from Highway 9. The golden sunlight was slowly growing dimmer and dimmer, as the temperature went from pleasant to chilly. Now I was afraid of running into a big cat, as we were now far into the forest with not a soul nearby. And that was strange. Since we had left Castle Rock, we had not seen a single hiker. I guess we really were out in the sticks.

Complete darkness had swallowed the trail. Now we were walking in pitch blackness, aside from the small bubbles of light that our cheap Duracell headlamps provided. Suddenly, to our left, a small yellow shack with animal-proofed trash cans breached through the solid darkness. Next to the trash cans sat a sign with a campfire crossed out in red. As we investigated further past the yellow outhouse, we saw little campsites littered around. Our spirits had been replenished. Wherever we were, it was a campsite. And better yet, not another soul was present. We ignored how strange that was and set up camp, nevertheless.

After the tent was up, Milla and I quickly got to work. Milla furnished the tent, setting up our sleeping bags, organizing our gear, and setting up lanterns to really lock in that home away from home vibe. Outside, I set up the remaining lanterns we brought, which was another example of dead weight; our headlamps were more than sufficient. I pulled out our little MSR cook set, excited to see it in action for the first time. The small pot held two bowls, two sporks, two cups, a little rag, and the tiniest stove I had ever seen. The MSR propane can was also small in size, so I was greatly surprised when I screwed the little stove on top of the canister and fired it up. The little thing had some major power, shooting out a torch-like flame with a thunderous roar. I placed water in the pot, carefully set it on the cooktop, and made my way toward the bathroom. I wanted to see if I could find out where we were.

“Wherever we were, it was a campsite.”

My goal was swiftly achieved. Not far from the yellow outhouse, a sign that said, “Waterman Gap Camp” lay just beyond the darkness. With this new information, we could finally figure out where exactly we were in relation to Big Basin. I walked to a nearby tree, relieved myself, and walked back to our camp. On my way back, I saw a few other campsites, but like all the others, they were vacant of hikers. At this point, I found that a little strange. It was peak season, and we were on one of the most famous backcountry hikes in the Bay Area. Huh? I thought.

Back at camp, the water was already boiling. I pulled out two dried food packets—one was beef stroganoff and the other a vegetarian chili. After reading the directions, I poured the scalding water into each pack and set the timer on my cellphone. Milla and I were a bit nervous as to how this new food experience would play out. While we waited, Milla pulled out her phone and pointed to Waterman Gap Camp on her All-Trails map. To both of our discouragement, we were just a little under halfway to Big Basin. We had walked nearly 9 miles that day.

The food was surprisingly really good. Our empty bodies gormandized our dinners. It was only 10 p.m., but we were exhausted. We hurriedly cleaned up our dishes and headed to the tent for a night of much-needed rest. Tomorrow would be another long day, but if we could get up early enough, maybe, just maybe, we could still make it the 18 miles or so to the end of the trail. I mean, people did the whole trail in a day. If we pushed super hard, we could make it, and although this unreasonable goal was ludicrous, I still believed it.